Some History Behind The Carillon

Our building, the Carillon, is over 60 years old, but its roots go back much further than that.

Beginnings

The Sister Servants of the Holy Spirit of Perpetual Adoration, commonly known as the “Pink Sisters” (for their rose-colored habits), is an order founded in Holland in 1896. As cloistered nuns, the Pink Sisters spend their lives in prayer, separated from the world at large. They came to the United States early in the last century, first to Philadelphia in 1915, and then to St. Louis in 1928. In 1953, Archbishop Ritter of St. Louis sought a location for a third convent. Bishop Reicher of Austin answered the call, and Sister Mary Salvatora was sent to Austin (staying with the Daughters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul at Seton Hospital (now Ascension Seton), named for St. Elizabeth Ann Seton) to search for a location. After many scouting excursions, she came upon an available 5-acre site near the top of a hill on Exposition Boulevard. The order acquired the property in November of that year.

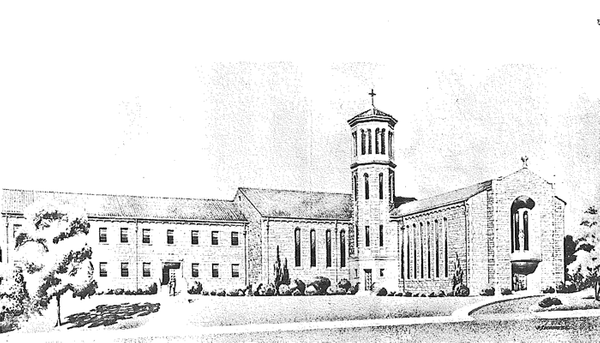

Construction

The sisters hoped to begin construction in 1955, but groundbreaking on the $800,000 convent and chapel was delayed until early 1957. The Adoration Convent of Divine Love opened a year and a half later, on June 5, 1958, with space for 50 sisters. Fifteen moved in at the time. There were two chapels – a private one for the cloistered sisters, and a public one, called the Adoration Chapel of Divine Love. A grilled wall separated the two chapels. The sisters maintained a perpetual prayer vigil in the chapels and converted the mesquite-filled land behind the convent into lovely, but private, gardens, that were surrounded by a 6 foot rock wall.

Five years after the convent opened, the “Friends of the Pink Sisters” held a fundraising drive to purchase two stained-glass windows. They completed a collection of 18 windows by 1964. The windows were crafted in Munich, Germany. Three represented the archangels and the rest depicted the mysteries of the rosary.

Problems Arise

When the convent was built, piers were driven through a layer of clay to bedrock, with about a foot of gravel separating the ground from a 10-inch slab of reinforced concrete that formed a basement floor. Unfortunately, the builders were unaware of the severity of water seepage that became apparent when the limestone “bedrock” was excavated for the basement portion of the building. As the clay moved, the gravel compressed, eventually causing the slab to swell and bulge. Because the concrete floor had been structurally tied to the walls with steel, the walls started to pull apart.

The sisters followed the advice of an advisory board, jackhammered around the perimeter of the basement floor to separate it from the walls, and tried to reroute the water seepage with French drains. In 1969, the Mother General of the order planned a visit, thinking it might be time to close the convent, given the high cost of permanent repairs and the relatively few sisters living in the convent. However, when she arrived, she decided the convent was too beautiful to close.

The Convent Closes

Beauty aside, the foundation problems, and lack of recruits, continued, and by the early 1980’s, the order decided to close the convent in order to devote its resources elsewhere. Tarrytown Baptist Church considered purchasing the property for parking and a seminary, but decided that the cost was too high. Eventually, the property was sold in 1983 to a local developer, Tom Francis, for approximately $2.2 million. The last public mass was held in the chapel on January 16, 1983. At the time, there were only 10 sisters left in the convent.

Homes and Offices Arise in Its Place

Francis originally acquired the property in order to develop the gardens into sites for single-family homes; the building was almost an afterthought. He considered donating the chapel, or even the convent itself, to an organization that could care for it. But eventually (probably due to the high cost of repairs for any nonprofit organization), the building was sold to another developer. Francis developed the gardens into the Hillview Green subdivision.

Timing was not the greatest for the developer of the building, and shortly after renovations began, the lender foreclosed on the building. The lender sought the assistance of Live Oak Development, which completed the conversion of the building property into Class A office space in 1986, and still owns the building today, as Live Oak. Reminders of the prior foundation problems are readily apparent in the cracks in the building’s exterior walls that have since been repaired.

The Carillon

For a number of years, Live Oak made the original public chapel available for use by various arts groups. When Live Oak outgrew their offices on the second floor, our firm moved into that space. (SNPA has been in this building since its inception in 1992, but was initially located on the ground floor). The majority of our space is located on a “new” second floor built in the middle of the sisters’ private chapel. In addition, large portions of the original garden wall remain, both in the building parking lot, and along the side of the Hillview Green subdivision on Hillview Road.

The Convent “Lives On”

The convent lives on not only through the care with which the building has been preserved, but also through its beautiful stained-glass windows. When the building was sold, the sisters carefully packed the windows with the intention of using them in a new convent planned for California. In the meantime, they were shipped to a convent in Lincoln, Nebraska, for storage. But the California convent failed to materialize, so in 1996, the three archangel windows were donated to a new church in North Platte, Nebraska. It seems fitting that this new church, St. Elizabeth Ann Seton Church, is named for the same saint as the hospital at which Sister Mary Salvatora was hosted during her search for a suitable location for the convent six decades ago. Groundbreaking for St. Elizabeth’s new permanent sanctuary that now serves as the home of those windows did not take place until April of 2010, and construction was completed in early 2012. Photos of the windows can be found here. You can also find photos of the exterior and interior of the sanctuary.

Acknowledgements

A special thanks to Live Oak, the Austin History Center, and Google, for providing us with much of the information found here.